By

Craig Boddington

Gobblers were going crazy just over a little rise. I duckwalked to the crest, peered over. Sure enough, a nice gobbler was right there. I held the bead where neck feathers ended and saw him down hard. Awesome! Another gobbler rushed in from the right, probably to pounce on this one. Swinging hard, I used the second barrel. Two fine Merriam’s gobblers…and the only “double” I’ve ever gotten on wild turkeys. At least on purpose…more about that later.

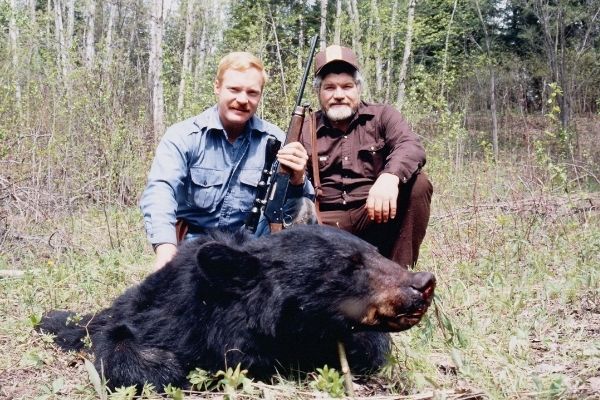

I wasn’t hunting turkeys; I was up there on a spring black bear hunt. While sitting over baits, I heard a lot of gobblers. The season was open, so I went to town and bought tags. I didn’t have a turkey gun with me, but I did have a Krieghoff 20-gauge sporting clays gun in the truck.

SHOT PLACEMENT

There were few turkeys in Kansas when I started hunting, so experience came long and slow. I still consider myself among the world’s worst turkey callers but, today, at least I have a fair amount of experience shooting turkeys.

About 30 years ago, before I’d ever taken an Eastern gobbler, I hunted in southern Missouri with a borrowed Browning BPS 10-gauge pump gun. Awesome shotgun, but I didn’t know the gun. We had a big gobbler strutting across a clearing, not 25 yards, but trees and brush between us. Believing a max-load 10-gauge could do anything, I pasted him square in the center of the chest.

He dropped and rolled behind a big oak. We ran forward and saw…nothing. No feathers, no indication which way he had gone. We walked lines in every direction, and never found a trace.

I had made fundamental mistakes. I’m pretty good with a shotgun but, although many have, I’ve never taken a turkey on the wing; all of my gobblers have been on the ground. This is different from most shotgunning; you must aim, rather than point and/or swing!

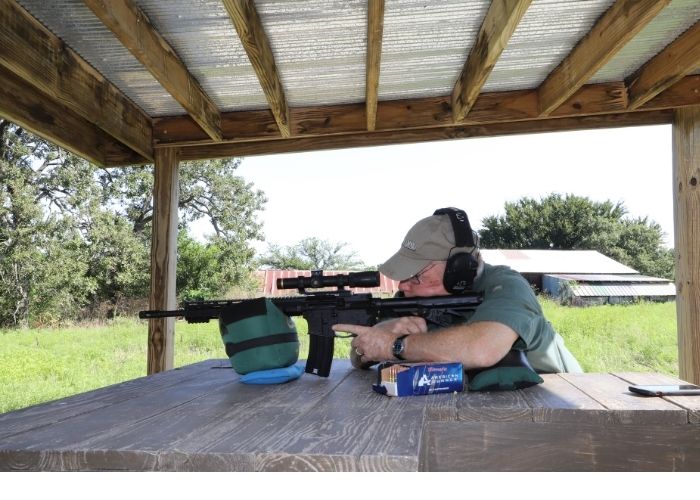

Have you taken your turkey gun to the range and aimed at a point target, to see exactly where your pattern lands in relation to the bead? You might be surprised at the results. Many shotguns high, others dead flat. Less commonly, a bit low, or even off to one side. Few of us are dumb enough to go deer hunting without checking a rifle on a target, but too many hunters get handed a shotgun and go turkey hunting. A shotgun charge is different than a single bullet, so we trust the pattern…without knowing exactly where the barrel directs it.

A turkey-hunting expert (which I am not), would never make such a mistake. Nor would he (or she) make the same basic shot-placement error. We can argue all day about gauges, shells, and chokes, but the turkey is a big, strong bird. Beyond point-blank range, no gauge, shell, or shot size can concentrate enough pellets to reliably take down a turkey with a body shot.

A facing presentation requires the greatest penetration. What I know now (and didn’t know then): You never shoot a strutting turkey with head down! You’re banking on a couple of “golden pellets” into the head and neck. If you don’t get them, there is little guarantee of getting enough penetration through feathers and flesh into the chest cavity. Side shots are only slightly better. The turkey is our “big game bird” and shot placement is essential. The proper shot is with the head and neck extended, the aiming point at the head, if horizontal; and where the neck joins the body if vertical. Then you can let the pattern do its work!

GAUGES

It’s really not a matter of how much shot (gauge and shot charge). It’s really a matter of choke, matching the load to the gun, and putting the charge in the right place. Expert turkey hunters (which I am not) are now having great fun—and success—head-shooting turkey with .410s, and 28 gauges, enabled by wonderfully advanced loads and chokes.

Absolutely can be done, but I have not opened that window. I’m not a good enough caller—or patient enough hunter—to go there. I went through my 10-gauge phase, but found that chokes, patterns, and shells weren’t as advanced—or as available—as for the popular 12 and 20 gauges. I’ve taken numerous turkeys with 20-gauges guns, plenty of gun…especially with the right shells in good chokes. However, I’m mostly a 12-gauge guy for turkeys.

With the shells, shot, and chokes we have today, I can’t imagine a shot I might take that a 12-gauge 3-inch load can’t handle. Son-in-law Brad Jannenga uses a Benelli Nova slide-action 3.5-inch 12-gauge, theoretically as effective as my old 10-gauge. Devastating…on both ends. Left-hand 3.5-inch 12-gauge guns being scarce, I’ve never used one. I don’t push the range, and my experience is the shorter shells, albeit with smaller shot charges, often deliver better patterns.

CHOKES AND SHOT

Taking turkeys cleanly isn’t about gauge or weight of charge, but pattern density. This is all about chokes! These days, interchangeable chokes are almost universal with new guns (even the side-by-side 10-gauge I used for years had choke tubes). Older guns, of course, have fixed chokes. Typically, you want a tight choke for turkeys but, depending on shot size and material (lead, bismuth, tungsten, steel), the tightest choke may not yield the tightest patterns in your gun. It’s important to know your pattern is tight and even, and that requires shooting at a target. Turkey loads are spendy and we don’t have a lot of shells to waste on paper. But, out of a 10-shell box of turkey loads, we can expend a couple, verifying point of impact and pattern.

For several years, my “go to” turkey gun has been a camouflaged Mossberg 500 12-gauge 3-inch left-hand pump gun. I’ve shot a bunch of turkeys with it, mostly with lead No. 5 or 6 shot. I was curious how it might pattern with tungsten, so I started with the Full choke tube I’ve been using. We know from using steel shot on waterfowl that, with extra-hard shot, we usually use more open chokes to achieve uniform density and avoid blowing the pattern.

My long-reliable Mossberg didn’t look great with Remington 3-inch No. 5 HD (tungsten). It looked worse with a Kent load of tungsten No. 7, lots of deep-penetrating pellets…but they still must land in the right place. I was over-choked with tungsten; the No. 7 load had a classic “hole in the pattern,” centered on the head of a life-size turkey target!

If I had shells to burn, I’d have changed chokes and tried again but, these days, who does? Conserving ammo, I tried the same two loads in a left-hand Franchi Affinity with Full choke tube. OMG, not shells or gun, just the choke! Remington’s No. 5 HD looked great, over 40 pellet strikes in head and neck at 25 yards. Kent’s No. 7 tungsten was even better; I couldn’t count the pellets in head and neck on the target!

As for shot size, personal preference. Today, some serious hunters are using shot as small as No. 9, relying on maximum pattern density for head shots only. I don’t go that small! I’ve taken a lot of turkeys with No. 6 shot (lead or bismuth) for head/neck shots, but I like No. 5 better, good pattern density, with greater pellet energy/penetration. Often, I’ll load No. 4 in the magazine or second barrel for a rarely-used follow-up.

Tungsten shot is a recent experiment for me. Denser than lead, penetration should be better for like shot sizes. Theoretically, No. 7 tungsten should penetrate about as well as lead No. 6. That Kent load is slow at 1000 fps, but carried an amazing 2.5 ounces of No. 7 tungsten pellets! It looked great on a target, and that week the Franchi, same choke with Kent No. 7, accounted for the heaviest Rio Grande gobbler I’ve ever taken.

WHAT ABOUT SIGHTS?

Since we aim at turkeys, sights are obviously good…to a point. The shot is rarely perfectly static, so it’s a mistake to get fixated on precision; you’re still working with a pattern, not a single projectile.

I had a red-dot sight on that Krieghoff 20-gauge for a while, and both Donna and I shot turkeys with it. Awesome! My Mossberg has a rudimentary rear sight on the rib, in conjunction with the fiber-optic front bead. Also wonderful, but if you use sights, don’t forget to check zero!

Just once, I put a low-power magnifying scope on a turkey gun. Seemed amazing, but there is a tunnel-vision effect to riflescopes. I shot a great gobbler, the big red head almost glowing through the scope. When I went to recover, there was another equally great gobbler stone-dead in thigh-high grass 10 yards farther! Two-bird area, so not a train smash, but definitely not my intention. Through the scope, with reduced peripheral vision, I never saw the bird behind mine. Open sights and red dots, good idea because turkey hunting is about shot placement…but that’s the only time I used a magnifying riflescope for turkeys!