By

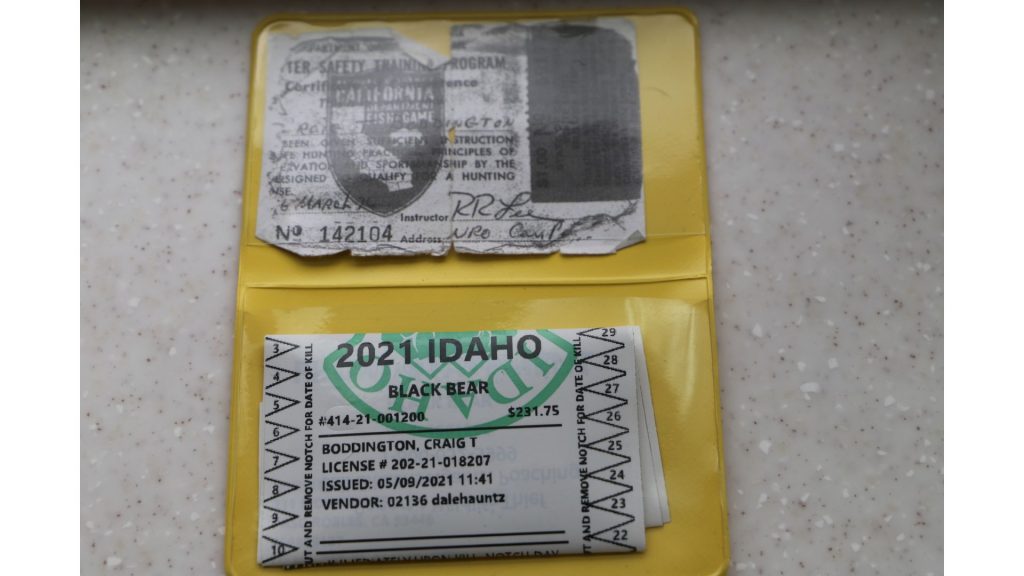

Craig Boddington

Throughout most of the country April is prime time for turkeys. I am not an expert turkey hunter, and a mediocre turkey caller…on my best days. No way I will write the definitive “how to” story on turkey hunting. However, given a chance, I’ve been pretty good at shooting turkeys.

Not perfect. (Talk about that later.) Wife Donna hasn’t taken as many turkeys and, theoretically, isn’t as good with a shotgun. Even so, she is 100 percent on bagging all turkeys she has shot at. She took her first Eastern gobbler in Georgia last Saturday, so her experience now includes three varieties, with some multiples.

On the other hand, my Dad was the best and fastest wingshooter I ever knew on quail and pheasants. Dad had been a successful fighter pilot in WWII and had off-the-charts vision. Despite these advantages, he couldn’t figure out how to hold a shotgun on a stationary bird and center a turkey’s head. His native Kansas had no turkeys for most of his life, so a wild turkey was one of few creatures he really wanted to take. I can’t recall how many turkeys he shot over until he finally took his first with a .22 Hornet (in Texas, where rifles are legal).

AIM A BIT LOW

Most shotguns are stocked to center the pattern a bit high for rising birds, so you can see the clay or the bird above the rib or bead. Some shoot “dead-on,” but few modern shotguns pattern below point-of-aim. Dad’s problem: A fast shooter on rising birds, he liked his shotguns to shoot high and wasn’t used to a stationary target. This exaggerates the effect of a high-shooting gun, and he couldn’t make himself place the bead far enough down on the neck to account for both the stationary target and the rise of the pattern.

You can check this with a pattern board, and you should. Checking “zero” and verifying patterns with a shotgun from a steady rest isn’t pleasant. Heavy turkey loads kick like hell, but it’s essential preparation.

What you want to see on a target: Most of the pattern just above the aiming point. Then, when a bird presents with a more-or-less vertical neck, you can place the bead about where the feathers stop and the naked, red neck starts. Remember, you’re dealing with a pattern, not a single bullet. The majority of the pattern should catch the entire head and neck.

Depending on what a target has revealed, you are probably okay aiming where the neck joins the body (Dad would have been). Height of comb varies; my turkey shotguns don’t shoot as high as my trap guns or quail guns. The main point: Don’t aim precisely at the head. With most shotguns, this is asking to shoot over the top. You must hold a bit low, down on the neck.

On April 1st, opening day in Georgia, we had a disappointing morning. Minimal distant gobbling shut off at dawn, and we never saw a bird. Nearly noon, set up in a different spot, a big gobbler came in completely silent. Just out of range but clearly eyeing our decoys, he started to strut—never gobbled—then advanced cautiously.

I always carry a rangefinder and check distances when I set up, so I’ll have a good idea when a gobbler is close enough. With the shotgun I carried, he’d probably been in range for a while, but he was strutting in weeds that almost covered him. Silent, obviously checking our set, but not comfortable. I was sure he was within 40 yards when he stood erect and stretched his neck.

On a stationary target, a high pattern keeps getting higher as range increases. I rested the Mossberg over my knee, held well down on the long neck, and pressed the trigger. The bird dropped into the weeds, gone, but he was right there, a last few wingbeats as I approached.

HEAD SHOTS ARE BEST

Years ago, I was hunting in Missouri with a borrowed Browning BPS 10-gauge, awesome shotgun. A big bird came straight to us, strutted, and I pasted him head-on at 25 yards with a 3 ½-inch shell, 2.5 ounces of shot. The bird dropped to the shot and flopped behind a big oak. My partner and I ran to it…and the bird was gone. No trace, never seen again.

Doesn’t matter what you’re shooting. Body shots on turkeys with shotguns are unreliable. Tough birds, thick feathers, heavy breast protecting the vitals. When in strut, the head is tucked in, and the temptation is to shoot for that big, black mass. Big mistake that I’ll never make again. Wait until the head extends, and aim for the head and neck

Drives purists insane, but some states still allow rifles. That’s a different deal; the head is too small a target, and often moving. Purists, please ignore this: Where legal, I get a huge kick out of sniping turkeys with a small rifle, .17 or .22 Magnum, .22 Hornet. Wait for the broadside shot and aim where the wing butt joins the body. Doesn’t mess up much meat, and effective. If you have that shot with a rifle, you also have the head shot with a shotgun.

The tricky part: If the head is extended horizontally, while the bird is gobbling, then you have only the head as a very small point target. Better know exactly how high your gun shoots, otherwise there’s increased risk of passing the whole pattern just over the top. I shot a big Gould’s turkey in Sonora with his neck stretched out, remembered to hold a bit low. Killed the bird—doesn’t take all that many pellets in the head—but most of the pattern went high.

The shot I much prefer is to have the neck erect. Still not a big target, but bigger. Ideally, you want pellet strikes in both head and neck. No one can say exactly how many strikes are needed. Where pellets impact is random, but you want multiple strikes—with penetration—in spine and brain. There are “golden pellets”: The one strike that centers the brain, but let’s not count on that.

CHOKES, GAUGES, SHELLS

Depending on range, shells, shot, and pattern, anything can work. I’ve taken turkeys with my Model 12 skeet gun, but it’s not a turkey gun. For years I used a short-barreled Spanish side-by-side 10-gauge with screw-in chokes. Lots of shot, should have been perfect, but tt was rarely as devastating as it should have been. Not much development in 10-gauge shells. The pattern board eventually showed me that, with available ammo, the pattern had holes a turkey could fly through. Cool gun, but I got rid of it. Tight chokes are best, but even patterns more important.

Today, we have better shells, better shot, and better chokes. The great turkey hunter, Dr. Warren Strickland, was the first guy I talked to who was killing his turkeys with a .410. Today, a lot of serious turkey addicts, with great shells and awesome chokes, use small gauges.

Sorry, I don’t. I’m neither a good enough caller, nor a confident enough turkey hunter, to bank on the small gauges. I mostly use a 12-gauge, but both Donna and I have taken numerous turkeys with 20-gauge guns. In 12-gauge, I’m comfortable with 2 ¾ or 3-inch shells; in 20-gauge, we use 3-inch loads.

I have also downsized on shot. Historically, I’ve usually used lead No. 5 or 6 for the first (preferably head) shot, backed up with No. 4 for a follow-up body shot if needed. New shot has changed the game. I was stunned when I heard about experienced hunters—like Dr. Strickland—shooting turkeys with shot as small as No. 9. Depends on the pattern, and the shot. This year, our Georgia gobblers were taken with No. 8 tungsten shot in Mississippi-loaded Apex shells. Tungsten is denser than lead, more small pellets in the pattern, with better penetration per pellet.

Remember, velocity is much the same from gauge to gauge, thus pellet energy the same. Performance is thus largely about choke and payload, which dictate range. With turkeys, the important things are to check point of impact and pattern with your gun and your load.

RANGE AND SIGHTS

Then, focus on that bright red head…and keep your shots within the distance your pattern density guarantees multiple head-neck strikes.

With the shells and chokes we have today, effective ranges have increased. For me, I don’t push the range envelope. Given a choice, I also don’t let birds get too close. Easy to miss when all you have is a ball of shot the diameter of your barrel. My ideal distance is 20 to about 40 yards. In that window, I have a good pattern to work with…and a bit of standoff to bring the gun to bear without spooking the bird.

Unlike most shotgunning, turkeys are usually taken by aiming precisely at a point, stationary target, as in rifle shooting. I prefer a gun with a rib to sight down, and a highly visible front bead. My Mossberg pump has rudimentary rear sight with fiber optic front, awesome.

Just once, I put a low-power magnifying scope on a turkey shotgun. I didn’t like the tunnel-vision effect, and found magnification unnecessary at turkey-shooting distance. I have experimented more with reflex (red-dot) sights. They are extremely effective, especially for older eyes, with increasing trouble resolving the front bead. If your shotgun has sights of any type, then it’s essential to, literally, check zero, adjusting the sight to ensure your pattern is exactly where you want it.