In rifle cartridges, it is said that the .35-caliber has never been popular. This is probably true, but must be taken in context. In the U.S., sales of all rifles and cartridges above .30-caliber fall off the cliff. This makes sense. The whitetail deer is the primary big-game animal for millions of American hunters. Circumstances are rare (if they exist!) where a larger caliber than the all-American .30 is needed to kill a deer.

Even so, there are many “over-.30” cartridges…before you get up to the highly specialized big-bore cartridges for dangerous game. The 8mm (.32-caliber or .323-inch bullet) has never done especially well over here. The .33 (.338-inch bullet) has done better, but even the .338 Winchester Magnum took off slowly because word got out that it was a hard kicker. No kidding? A marvelous elk cartridge, the .338 Winchester Magnum is not a deer cartridge. From there you step up to the European 9.3mm (.366-inch) and .375. I love various cartridges in both diameters and often use them in Africa, but their utility in North America is limited. Often overlooked, there is a rich tradition of .35-caliber cartridges.

Both Remington and Winchester have long histories with .35s. Introduced in 1906 and still loaded, the .35 Remington is the longest-running .35. Slow and with mild recoil, its heavy 200-grain bullet made its bones as a deep-woods thumper for whitetails and black bears.

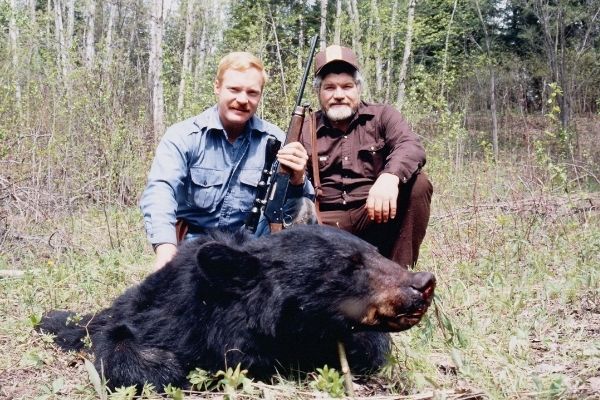

A half-century passed before Remington introduced another .35! The .350 Remington Magnum (1965) was ahead of its time, a short magnum designed for short bolt-actions. In Remington’s too-light M600 carbine the .350 Remington Magnum was a hard-kicking beast. It never had a chance, although it has become almost a cult cartridge among black bear hunters. I had a .350 Remington Magnum on a left-hand short-action M700. Built by MGA, it was light…but not too light, and very effective.

Based on the .30-06 case necked up, the .35 Whelen was developed in 1922. It persisted as a fairly common wildcat, finally legitimized by Remington in 1988. The previous fall, I took one of the prototypes to Alaska and flattened a huge moose with a quartering-to shot. Using a 250-grain round-nose, I will never forget how that big animal went over backwards. Since then, the .35 Whelen has become a fairly standard cartridge, great for elk and capable up to big bears, but without magnum recoil or blast.

Winchester has even deeper ties to the .35. Their first, the .35 Winchester, was introduced in 1903 in the 1895 lever-action. The weak .35 Winchester Self-Loading (WSL) was introduced in their semiautomatic M1905. Two years later, they beefed up both the rifle and cartridge with the Winchester 1907 and .351 WSL. Although reliable, these early Winchester self-loaders used blow-back actions, and couldn’t house cartridges as powerful as Remington’s Model 8 (and its .35 Remington).

At heart, Winchester was a lever-action company. In the mid-1930s, they wanted to replace both the Winchester M1886 and its .33 Winchester; and the M1895 in .35 Winchester with a faster, more powerful cartridge…in a less expensive tubular magazine lever-action. The result was the .348 Winchester in the M71. Arguably a “.35,” the .348 was the fastest factory cartridge ever housed in a tubular-magazine lever-action.

The .348 remains legendary, but its time had passed; the big, rimmed case was never adapted to any other factory rifles. The top-eject M71 resists conventional scope mounting, and until Hornady’s FTX bullet, blunt-nosed bullets with poor aerodynamics were mandatory.

Belatedly seeing the writing on the wall, in 1955 Winchester introduced the .358 Winchester in the M88. The cartridge was intended to replace the .348, the rifle to replace the M71. With side ejection (conventional scope mounting), box magazine (spitzer bullets), and forward-locking rotating bolt, the M88 was Winchester’s fourth most popular lever-action, after Models 1894, 1892, and 1873. The .358 didn’t do as well; it’s an uncommon chambering, and that’s a shame. It’s a wonderful little cartridge, efficient and powerful. I’ve had several .358s and want to get another! Unfortunately, the .358 was born in the first magnum craze, when Americans craved velocity; the .358 just isn’t fast. Browning’s BLR is the last factory .358.

The .358 deserves more popularity, but it did better than Winchester’s next .35. Introduced in 1982, the .356 Winchester is essentially a semi-rimmed version of the .358, designed for a beefed-up version of the M1894. At the muzzle, the .356 is much the same as the .358, but it quickly falls behind because its blunt-nosed bullets. My friend Paul Cestoni has one and swears by it for close-cover hunting (why not), but it’s a rare bird.

I was surprised when Winchester tried again with 2019’s .350 Legend. Some folks groused about the name, suggesting that “legends” are earned. Hey, cartridges must have names! I prefer a recognizable name to confusing alphabet soup, and Winchester has a history of whimsical cartridge names, including Bee, Swift, and Zipper.

The .350 Legend is a clever cartridge. Winchester calls it “purpose-driven.”: A short-range deer cartridge that takes advantage of “straight-wall cartridges for deer” legislation, adaptable to current rifle platforms.

In the many states that required shotguns (or muzzleloaders) for deer, the intent was always to limit projectile distance. With whitetails overpopulated and increased hunter participation desirable, five former “shotgun states” allow “straight-wall” cartridges in some seasons or areas.

Criteria and dimensions are tight. Old rifle cartridges like .38-55 and .45-70 usually fall into line. Until the Legend, the primary “modern” alternative was the .450 Bushmaster. When Ruger chambered their bolt-action American to Bushmaster, they saw a huge spike in sales in Michigan alone! Problem: The hard-kicking Bushmaster is too much gun for many.

Enter the Legend. With hunting bullets of 155 to 170 grains and velocities averaging about 2200 fps, .350 Legend is in league with the .30-30 and .35 Remington. This is not damning with faint praise, but those classic deer cartridges have bottleneck cases, so cannot be used in “straight wall” states. Like the .30-30 and .35 Remington, the Legend is (at best) a 200-yard deer cartridge. That’s what it’s supposed to be and, that beats the effective range of most slug guns and muzzleloaders!

Using a rebated .223 rim with overall length of 2.25 inches, the Legend fits in the AR15 action, and is readily adaptable to bolt-actions. It uses 9mm diameter (.357-inch), enabling inexpensive target ammo loaded with pistol bullets.

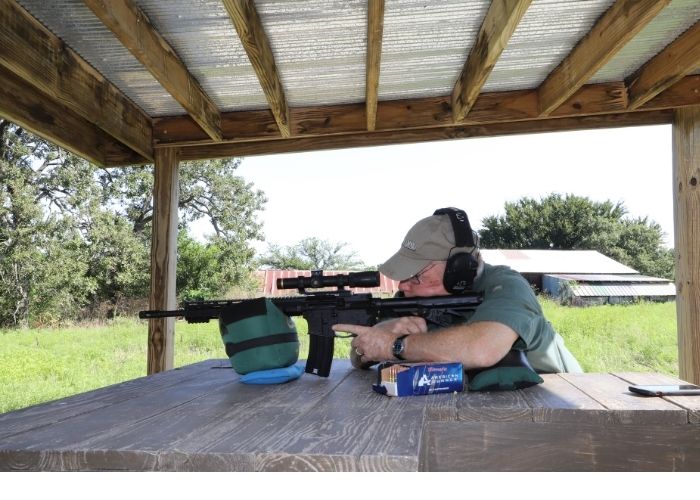

If you hunt where centerfire rifles are legal for deer, this straight-wall thing probably isn’t a big deal. It’s huge for deer hunters who “make do” with slug guns! Initial acceptance has been dramatic, leading to an unusually wide selection of loads for a new cartridge. I apply for deer in Iowa, so I bought a basic Mossberg Patriot in .350 Legend. So far, accuracy isn’t dramatic, but plenty good for the cartridge’s effective range. I haven’t yet hunted deer with it, but I used it on several Texas hogs. Recoil and report are mild and, with large frontal area, it hits hard…though not as hard as a .348 or .358. Nor should it; both of those cartridges are faster and carry more energy. Next spring, I intend to use the Legend on a black bear. It seems to me the .35s go together with boars and bears like peas and carrots!

.35 BULLET DIAMETERS AND THE “MISSING LINK”

Most American (and all Remington) “.35” rifle cartridges have used .358-inch bullets. Winchester has not been so consistent; the .35 and .358 Winchester do, but the .35 WSL used a .351-inch bullet, and the .351 WSL uses .352-inch. The .348 Winchester is also oddball, using a literal .348-inch bullet. European “.35” rifle cartridges (as in 9×57 Mauser) used the 9mm designation, so the same .357-inch bullet at the .350 Legend.

Missing from the .35-caliber lineup has been an extra-fast .35, but not without effort; there have been several proprietaries and wildcats. This probably starts with the .350 Rigby Magnum (1908). A century ago, Charles Newton’s proprietary .35 Newton had a following, as did the .350 Griffin & Howe Magnum (based on the .375 H&H case). Layne Simpson followed up his 7mm Shooting Times Western with the .358 Shooting Times Alaskan. It didn’t progress past wildcat form and, so far, neither has the 36 Nosler. The .358 Norma Magnum is a factory cartridge. It never caught on, but Schultz & Larsen and Husqvarna offered rifles.

Other than recoil and redundancy with established .33s, one reason why a fast .35 has never “made it”: With proper bullets, it would be adequate for just about anything but, unlike the 9.3mms and .375s, .35-caliber is generally not “street-legal” for larger African game.